Teachers know what many professionals do not: that there is no one syndrome of ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder) but many; that ADD rarely occurs in "pure" form by itself, but rather it usually shows up entangled with several other problems such as learning disabilities or mood problems; that the face of ADD changes with the weather, inconstant and unpredictable; and that the treatment for ADD, despite what may be serenely elucidated in various texts, remains a task of hard work and devotion. There is no easy solution for the management of ADD in the classroom, or at home for that matter. after all is said and done, the effectiveness of any treatment for this disorder at school depends upon the knowledge and persistence of the school and the individual teacher.

Here are a few tips on the school management of the child with ADD. The following suggestions are intended for teachers in the classroom, teachers of children of all ages. Some suggestions will be obviously more appropriate for younger children, others for older, but the unifying themes of structure, education, and encouragement pertain to all.

First of all, make sure what you are dealing with really is ADD. It is definitely not up to the teacher to diagnose ADD, but you can and should raise questions. Specifically, make sure someone has tested the child's hearing and vision recently, and make sure other medical problems have been ruled out. Make sure an adequate evaluation has been done. Keep questioning the SENCo until you are convinced.

Second, build your support. Being a teacher in a classroom where there are two or three kids with ADD can be extremely tiring. Make sure you have the support of the school and the parents. Make sure there is a knowledgeable person with whom you can consult when you have a problem (learning specialist, child psychiatrist, social worker, educational psychologist, pediatrician - the person's degree doesn't really matter. What matters is that he or she knows lots about ADD, has seen lots of kids with ADD, knows their or her way around a classroom, and can speak plainly.) Make sure the parents are working with you. Make sure your colleagues can help you out.

Third, know your limits. Don't be afraid to ask for help. You, as a teacher, cannot be expected to be an expert on ADD. You should feel comfortable in asking for help when you feel you need it.

ASK THE CHILD WHAT WILL HELP. Children can often tell you how they can learn best if you ask them. They are often too embarrassed to volunteer the information because it can be rather eccentric. But try to sit down with the child individually and ask how he or she learns best. By far the best "expert" on the how the child learns best is the child himself or herself. It is amazing how often their opinions are ignored or not asked for. In addition, especially with older kids, make sure the child understands what ADD is. This will help both of you a lot.

Having taken the aboveinto account, try the following:

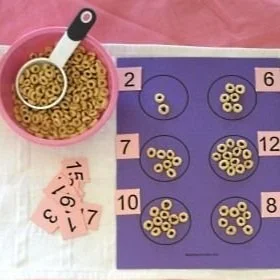

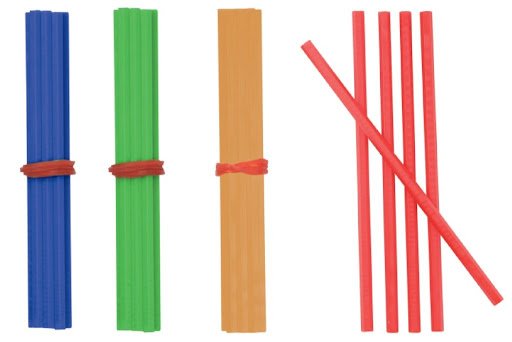

Remember that ADD kids need structure. They need their environment to structure externally what they can't structure internally on their own. Make lists. Children with ADD benefit greatly from having a table or list to refer back to when they get lost in what they're doing. They need reminders. They need previews. They need repetition. They need direction. They need limits. They need structure.

REMEMBER THE EMOTIONAL PART OF LEARNING. These children need special help in finding enjoyment in the classroom, mastery instead of failure and frustration, excitement instead of boredom or fear. It is essential to pay attention to the emotions involved in the learning process.

Post rules. Have them written down and in full view. The children will be reassured by knowing what is expected of them.

Repeat directions. Write down directions. Speak directions. Repeat directions. People with ADD need to hear things more than once.

Make frequent eye contact. You can "bring back" an ADD child with eye contact. Do it often. A glance can retrieve a child from a daydream or give permission to ask a question or just give silent reassurance.

Seat the ADD child near your desk or wherever you are most of the time. This helps stave off the drifting away that so bedevils these children.

Set limits, boundaries. This is containing and soothing, not punitive. Do it consistently, predictably, promptly, and plainly. DON'T get into complicated, lawyer-like discussions of fairness. These long discussions are just a diversion. Take charge.

Have as predictable a schedule as possible. Post it on the blackboard or the child's desk. Refer to it often. If you are going to vary it, as most interesting teachers do, give lots of warning and preparation. Transitions and unannounced changes are very difficult for these children. They become discombobulated around them. Take special care to prepare for transitions will in advance. Announce what is going to happen, then give repeat warnings as the time approaches.

Try to help the kids make their own schedules for after school in an effort to avoid one of the hallmarks of ADD: procrastination.

Eliminate or reduce frequency of timed tests. There is no great educational value to timed tests, and they definitely do not allow many children with ADD to show what they know.

Allow for escape valve outlets such as leaving class for a moment. If this can be built into the rules of the classroom, it will allow the child to leave the room rather than "lose it," and in so doing begin to learn important tools of self-observation and self-modulation.

Go for quality rather than quantity of homework. Children with ADD often need a reduced load. As long as they are learning the concepts, they should be allowed this. They will put in the same amount of study time, just not bet buried under more than they can handle.

Monitor progress often. Children with ADD benefit greatly from frequent feedback, it helps keep them on track, lets them know what is expected of them and if they are meeting their goals, and can be very encouraging

Break down large tasks into small tasks. This is one of the most crucial of all teaching techniques for children with ADD. Large tasks quickly overwhelm the child and he recoils with an emotional "I'll-NEVER-be-able-to-do-THAT" kind of response. By breaking the task down into manageable parts, each component looking small enough to be do-able, the child can sidestep the emotion of being overwhelmed. In general, these kids can do a lot more than they think they can. By breaking tasks down, the teacher can let the child prove this to himself or herself. With small children this can be extremely helpful in avoiding tantrums born of anticipatory frustration. And with older children it can help them avoid the defeatist attitude that so often gets in their way. And it helps in many other ways, too. You should do it all the time.

Let yourself be playful, have fun, be unconventional, be flamboyant. Introduce novelty into the day. People with ADD love novelty. They respond to it with enthusiasm. It helps keep attention - the kids' attention and yours as well. These children are full of life - they love to play. And above all they hate being bored. So much of their "treatment" involves boring stuff like structure, schedules, lists, and rules, you want to show them that those things do not have to go hand in hand with being a boring person, a boring teacher, or running a boring classroom. Every once in a while, if you can let yourself be a little bit silly, that will help a lot.

Still gain, watch out for overstimulation. Like a pot on the fire, ADD can boil over. You need to be able to reduce the heat in a hurry. The best way of dealing with chaos in the classroom is to prevent it in the first place.

Seek out and underscore success as much as possible. These kids live with so much failure, they need all the positive handling they can get. This point cannot be overemphasized: these children need and benefit from praise. They love encouragement. They drink it up and grow from it. And without it, they shrink and wither. Often the most devastating aspect of ADD is not the ADD itself, but the secondary damage done to self-esteem. So water these children well with encouragement and praise.

Memory is often a problem with these kids. Teach them little tricks like mnemonics, flashcards, etc. They often have problems with what Mel Levine calls "active working memory", the space available on your minds table, so to speak. Any little tricks you can devise - cues, rhymes, codes and the like- can help a great deal to enhance memory.

Use outlines. Teach outlining. Teach underlining. These techniques do not come easily to children with ADD, but once they learn the techniques it can help a great deal in that they structure and shape what is being learned as it is being learned. This helps give the child a sense of mastery DURING THE LEARNING PROCESS, when he or she needs it most, rather than the dim sense of futility that is so often the defining emotion of these kids' learning process.

Announce what you are going to say before you say it. Say it. Then say what you have said. Since many ADD children learn better visually than by voice, if you can write what you're going to say as well as say it, that can be most helpful. This kind of structuring glues the ideas in place.

Simplify instructions. Simplify choices. Simplify scheduling. The simpler the verbiage the more likely it will be comprehended. And use colourful language. Like colour coding, colourful language keeps attention.

Use feedback that helps the child become self-observant. Children with ADD tend to be poor self-observers. They often have no idea how they come across or how they have been behaving. Try to give them this information in a constructive way. Ask questions like, "Do you know what you just did?" or "How do you think you might have said that differently?" or "Why do you think that other girl looked sad when you said what you said?" Ask questions that promote self-observation.

Make expectations explicit.

A point system is a possibility as part of behavioural modification or reward system for younger children. Children with ADD respond well to rewards and incentives. Many are little entrepreneurs.

If the child seems has trouble reading social cues - body language, tone of voice, timing and the like - try discreetly to offer specific and explicit advice as a sort of social coaching. For example, say, "Before I tell your story, ask to hear the other person's first," or, "Look at the other person when he's talking." Many children with ADD are viewed as indifferent or selfish, when in fact they just haven't learned how to interact. This skill does not come naturally to all children, but it can be taught or coached.

Teach test-taking skills.

Make a game out of things. Motivation improves ADD.

Separate pairs and trios, whole clusters even, that don't do well together. You might have to try many arrangements.

Pay attention to connectedness. These kids need to feel engaged, connected. As long as they are engaged, they will feel motivated and be less likely to tune out.

Try a home-to-school home notebook. This can really help with the day-to-day parent-teacher communication and avoid the crisis meetings. It also helps with the frequent feedback these kids need.

Try to use daily progress reports.

Encourage and structure for self-reporting, self-monitoring. Brief exchanges at the end of class can help with this. Consider also timers, buzzers, etc.

Prepare for unstructured time. These kids need to know in advance what is going to happen so they can prepare for it internally. If they are suddenly given unstructured time, it can be over-stimulating.

Prepare for unstructured time. These kids need to know in advance what is going to happen so they can prepare for it internally. If they suddenly are given unstructured time, it can be over-stimulating.

Praise, stroke, approve, encourage, nourish.

With older kids, have then write little notes to themselves to remind them of their questions. In essence, they take notes not only on what is being said to them, but what they are thinking as well. This will help them listen better.

Handwriting is difficult for many of these children. Consider developing alternatives. Learn how to use a keyboard. Dictate. Give tests orally.

Be like the conductor of a symphony. Get the orchestra's attention before beginning (You may use silence, or the tapping of your baton to do this.) Keep the class "in time" , pointing to different parts of the room as you need their help.

When possible, arrange for student to have a "study buddy" in each subject, with phone number (adapted from Gary Smith).

Explain and normalize the treatment the child receives to avoid stigma.

Meet with parents often. Avoid pattern of just meeting around problems or crises.

Encourage reading aloud at home. Read aloud in class as much as possible. Use story-telling. Help the child built the skill of staying on one topic.

Repeat, repeat, repeat.

Exercise. One of the best treatments for ADD in both children and adults, is exercise, preferably vigorous exercise. Exercise helps work off excess energy, it helps focus attention, it stimulates certain hormones and neurochemicals that are beneficial, and it is fun. Make sure the exercise IS fun, so the child will continue to do it for the rest of his or her life.

With older children, stress preparation prior to coming into class. The better idea the child has of what will be discussed on any given day, the more likely the material will be mastered in class.

Always be on the lookout for sparking moments. These kids are far more talented and gifted than they often seem. They are full of creativity, play, spontaneity, and good cheer. They tend to be resilient, always bouncing back. They tend to be generous of spirit, and glad to help out. They usually have a "special something" that enhances whatever setting they're in. Remember, there is a melody inside that cacophony, a symphony yet to be written.