Educational analysis of handwriting

This paper is concerned with the analysis of handwriting from an educational perspective, with a view to understanding the difficulties that a student may be experiencing in connection with writing by hand at school, college or university. It will address the assessment of hand writing using standardised tests which are readily available to teachers and other professionals as well as describing how a standardised test of handwriting can be enhanced and supplemented using dynamic assessment techniques and describe how handwriting can be assessed without use of standardised tests.

The first step is to gather hand writing samples. This can be done using standardised tests or using dynamic assessment techniques. The Detailed Assessment of Speed of Handwriting (DASH), and its sister test, the Detailed Assessment of Speed of Handwriting 17+ (DASH 17+) are the standardised tests that my organisation has settled on.

The DASH is used to measure the handwriting speed of students from nine years to 17 years of age. The DASH 17+ is used to measure the speed of handwriting of students from 17 years of age up to a test ceiling of 24 years 11 months. This does not mean that the test cannot be used on students who are older than the test ceiling, although a note should be included when reporting the results that the scores are not offered as a truly standardised and accurate score.

The DASH and DASH 17+ tests the handwriting speed of a student under four different stresses: copying best, alphabet writing, copying fast and free writing.

The sub-test scores for all four can be cumulated in order to derive a standard score with associated percentile.

After the administration of a standardised test of handwriting speed you may wish to explore the student’s handwriting further using dynamic assessment techniques. Alternatively you may not have standardised tests available or have objections to standardised tests. If so the use of dynamic assessment techniques is very powerful. While this approach will not offer a standardised and statistically reliable score, it can allow students to produce a writing sample at a level more relevant to them than is required by the DASH.

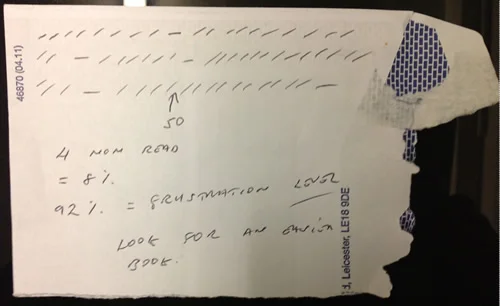

To gather samples of a child or adults handwriting without use of standardised tests. First type the standard sentence containing all letters of the English alphabet: The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog and print it out (Aerial 18). Organise some sentences which will be presented visually at distance to emulate copying from the white board etc. during lessons/lectures. Provide the student with pen and lined paper and ask them to:

copy the standard sentence in their best handwriting repeatedly for one minute.

copy the standard sentence in their fastest handwriting repeatedly for one minute.

copy from distance for one minute.

free write about something simple, such as their day so far (low cognitive demand). Allow five minutes for this with one minute for planning.

free writing about something complex (high cognitive demand). This task needs to be appropriately challenging and set in relation the student and their course of study. The task would be the equivalent to an examination question. Explain that they will need to spend 10 minutes on this task. Allow two minutes for planning.

Write to dictation (for secondary age students and above only). Take your dictation sample from a text book they are currently using.

If a student has fast, average or generally slow handwriting it is likely that the words written per minute will be similar for each sample. If using a standardised test very accurate tables will be available to you. If using dynamic techniques the following writing speeds offer a rough rule of thumb:

Age WPM

9 10

10 12

11 14

12 16

13 18

14 20

15 22

16 24

Adult 25

Analysing the Results and Intervention.

If you conclude that the writing speed is slow, then it may be useful to discuss making an alternative method of recording such as through typing or using dictation software as the main method of recording at school, college or university. To facilitate the effectiveness of this intervention it may be necessary for the student to further develop their touch typing skills such as through typing club.

Analysis of spelling error. You may wish to analysis the free writing sample for spelling errors under the following types.

phonetic errors: This type of error may occur due to phonetic attempts to spell a word, for example, ‘right’ may be spelled as ‘riyt’. omitting suffixes: for example, I am go to the park. Rather than I am going to the park.

During the hand writing sampling students may balk, become distressed or present behaviours that indicate they are under stress. If so stop testing. If this happens during the copying samples, an exploration of alternative ways of recording would be an appropriate intervention, this could include dictation using a scribe or voice recognition software, use of a personal computing device: lap top, net book, tablet. If it occurs during the free writing samples then further training in academic planning skills with some additional time in examinations (if possible) would be a useful intervention.

It is useful to report the student’s pen grip. There is a progression in pencil grasp from early childhood onwards Schneck and Henderson (1990). In general pen holds are broken down into functional and inefficient grasp.

Functional Grasp Patterns

Tripod grasp with open web space: The pencil is held with the tip of the thumb and index finger and rests against the side of the third finger. The thumb and index finger form a circle.

Quadripod grasp with open web space: The pencil is held with the tip of the thumb, index finger, and third finger and rests against the side of the fourth finger. The thumb and index finger form a circle.

Adaptive tripod or D'Nealian grasp: The pencil is held between the index and third fingers with the tips of the thumb and index finger on the pencil. The pencil rests against the side of the third finger near its end.

Immature Grasp Patterns

Fisted grasp: The pencil is held in a fisted hand with the point of the pencil on the fifth finger side on the hand. This is typical of very young children.

Pronated grasp: The pencil is held diagonally within the hand with the tips of the thumb and index finger on the pencil. This is typical of children ages 2 to 3.

Inefficient Grasp Patterns

Five finger grasp: The pencil is held with the tips of all five fingers. The movement when writing is primarily on the fifth finger side of the hand.

Thumb tuck grasp: The pencil is held in a tripod or Quadripod grasp but with the thumb tucked under the index finger.

Thumb wrap grasp: The pencil is held in a tripod or Quadripod grasp but with the thumb wrapped over the index finger.

Tripod grasp with closed web space: The pencil is held with the tip of the thumb and index finger and rests against the side of the third finger. The thumb is rotated toward the pencil, closing the web space.

Finger wrap or inter digital brace grasp: The index and third fingers wrap around the pencil. The thumb web space is completely closed.

Flexed wrist or hooked wrist: The pencil can be held in a variety of grasps with the wrist flexed or bent. This is more typically seen with left-hand writers but is also present in some right-hand writers.

On occasion difficulties may be identified that will necessitate onward referral to an educational psychologist or occupational therapist. For instance, if the percentage of illegible words exceeds 25% then there is a strong likelihood that an educational psychologist or occupational therapist may consider a diagnosis of dysgraphia supported by the results of test instruments such as the Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration (Beery VMI) this would enable an assessment of the underlying skills associated with the development of hand writing to be explored.

References:

https://www.typingclub.com/

Beery, K.E. & Beery, N.A. (2010) The Beery-Buktencia Developmental Test of Visual Perception and Motor Coordination. Bloomington: Pearson (6th ed.).

Frith, U., 1982. Cognitive Processes in Spelling and their Relevance to Spelling Reform. Spelling Progress Bulletin, 6-9.

Handwriting Identification: Facts and Fundamentals Roy A. Huber, Alfred M. Headrick 1999 crc press LLC

JCQ/AA/LD Form 8. Application for access arrangements – Profile of learning difficulties

Min, K., Wilson, W.H., Moon, Y., 2000. Typographical and Orthographical Spelling Error Correction. LREC Conference.

Spelling Progress Bulletin, Summer 1983, pp14-16] Spelling and Handwriting: Is there a Relationship?,by Michael N. Milone, Jr, Ph.D. James A. Wilhide, and Thomas M, Wasylyk** Zaner-Bloser, Inc., Honesdale, PA.

SpLD Working Group 2005/DfES Guidelines.

Varnhagen, C.K., Varnhagen, S., Das, J.P. 1992. Analysis of Cognitive Processing and Spelling Errors of Average Ability and Reading Disabled Children. Reading Psychology, 17(3): 217-239.